The Fukushima disaster, the most severe nuclear accident since the 26 April 1986 Chernobyl disaster, began on March 11, 2011 after a massive offshore earthquake produced a tsunami that washed ashore and damaged the backup generators of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which is located on the Eastern shore of Japan’s Honshu Island, the largest island of Japan. The tsunami generated a 14-meter-high wall of water that swept over the plant’s seawall and flooded the plant’s lower grounds around the Units 1–4 reactor buildings with sea water, filling the basements and knocking out the emergency generators.

Contrary to the Chernobyl disaster (1986) this disaster happened in multiple reactors at once – and is still ongoing.

What happened after the earthquake?

After detecting the earthquake, the active reactors automatically shut down their fission reactions. The electricity supply failed, and the reactors’ emergency diesel generators automatically started. Critically, they were powering the pumps that circulated coolant through the reactors’ cores to remove decay heat, which had continued after fission had ceased.

Satellite image of damage at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan following the March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami.

Source: DigitalGlobe

Water quickly flooded the low-lying rooms in which the emergency generators were housed. The flooded diesel generators failed soon afterwards, resulting in a loss of power to the critical coolant water pumps. These pumps were needed to continuously circulate coolant water through the reactors for several days to keep the fuel rods from melting, as the fuel rods continued to generate decay heat after the SCRAM event. The fuel rods would become hot enough to melt during the fuel decay time period if an adequate heat sink was not available.

After the secondary emergency pumps (run by back-up electrical batteries) ran out, one day after the tsunami on March 12th, the water pumps stopped and the reactors began to overheat. These events led to three nuclear meltdowns, three hydrogen explosions and the release of radioactive contamination in Units 1,2 and 3 between March 12th and 15th.

TIP: Do you want to visit Fukushima the most safest way? Book your tour with ChernobylX now!

Evacuation

After the declaration of a nuclear emergency by the Government on 11 March, the Fukushima prefecture ordered the evacuation of an estimated 1,864 people within a distance of 2 km from the plant.

Source: Fukushima pref. website

The Guardian reported on 12 March that residents of the Fukushima area were advised “to stay inside, close doors and windows and turn off air conditioning. They were also advised to cover their mouths with masks, towels or handkerchiefs” as well as not to drink tap water.

Then the government set in place a four-stage evacuation process: a prohibited access area out to 3 km, an on-alert area 3–20 km and an evacuation prepared area 20–30 km.

Over 50,000 people were evacuated during 12 March. The figure increased to 170,000–200,000 people on 13 March, after officials voiced the possibility of a meltdown.

Evacuees from the radiation zone have reported that some evacuation shelters, including ones run by the city of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, had refused to allow them entrance to their facilities, claiming that the evacuees could be carrying radioactive contamination with them. The shelters have required the evacuees to present certificates obtained by the government of Fukushima prefecture stating that the evacuees are “radiation free”.

Abandoned house inside Fukushima disaster zone.

Photo: Xtours

By September 2011, more than 100,000 Fukushima Prefecture residents had left their homes, did not return to Fukushima prefecture as other evacuees. Some locations near the crippled nuclear power plant are estimated to be contaminated with accumulated radiation doses of more than 500 millisieverts a year, diminishing residents’ hopes of returning home anytime soon. Even areas away from the nuclear plant are still suffering from a sharp decline in tourism and sluggish financial conditions.

FUKUSHIMA’S NUCLEAR EXCLUSION ZONE

The map shows the nuclear exclusion zones around Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc./Kenny Chmielewski

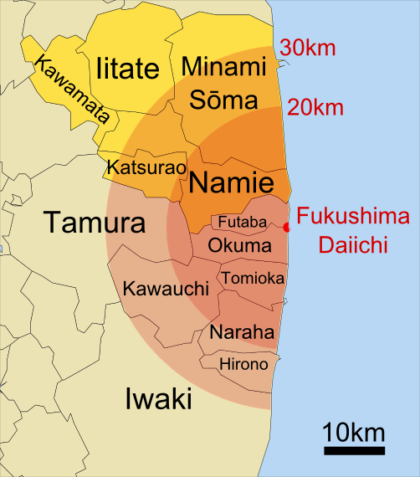

Due to concerns about possible radiation exposure, government officials established a 30 km no-fly zone around the facility, and the land area within a radius of 20 km around the plant, covering an area of 600 square km, was evacuated. In a third area that extended to a radius of 30 km around the plant, residents were asked to remain indoors.

As more information about the path of the fallout emerged, 207 square km of land northwest of the initial exclusion zone were also declared dangerous by the Fukushima prefectural government and included in the greater exclusion zone (which increased the total area off-limits to 807 square km).

Fukushima I and II Nuclear Accidents Overview Map showing evacuation and other zone progression and selected radiation levels.

Source: Wikipedia

There are three levels of restriction zone:

- Difficult-to-return Zone

- Annual integrated doses are over 50mSv.

- Entry is prohibited with some exceptions.

- Lodging is prohibited

- Restricted residence Zone

- Annual integrated doses are between 20mSv and 50mSv.

- Entry is permitted, and business operation is partially permitted.

- Lodging is prohibited with some exceptions.

- Evacuation order cancellation preparation Zone

- Annual integrated doses are below 20mSv.

- Entry is permitted, and business operation is permitted.

- Lodging is prohibited with some exceptions.

However, starting in August 2015, some areas in the greater exclusion zone that had earlier been declared contaminated were considered safe enough for former residents to either visit their homes and businesses for short periods, or return to them permanently. By 2017, the exclusion zone had declined to 143 square miles (371 square km).

Abandoned shop store inside ghost town Namie, Fukushima, Japan.

Photo: Xtours

Despite this seemingly good news, few people have returned so far, most of them elderly. Some studies investigating the effects of the Fukushima nuclear disaster on birds and insects have reported population declines in some species, as well as declines in overall biodiversity among these groups in the exclusion zones. However, as in Chernobyl, some populations of persecuted wild animals, such as wild boar, have increased.

RELEASE AND DISSEMINATION FOR RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS

Regarding to the studies, there was a release of harmful radioactive pollutants or radionuclides, such as iodine‑131 (which has a half-life of 8 days), cesium‑134, cesium‑137 (which has a 30-year half-life), strontium‑90, and plutonium‑238 and many others.

Japanese cities, towns and villages around the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The 20km and 30km areas had evacuation and sheltering orders, respectively. Later, more evacuation orders were given beyond 20 km in areas northwest of the site. This affected portions of the administrative districts highlighted in yellow.

Source: Wikipedia

A significant problem in tracking radioactive release was that 23 out of the 24 radiation monitoring stations on the plant site were disabled by the tsunami. There is some uncertainty about the amount and exact sources of radioactive releases into the air.

Major releases of radionuclides, including long-lived caesium, occurred in air, mainly in mid-March 2011. The population within a 20km radius had been evacuated three days earlier.

https://www.tepco.co.jp/en/hd/index-e.html

By the end of 2011, Tepco had checked the radiation exposure of 19,594 people who had worked on the site since 11 March. For many of these both external dose and internal doses (measured with whole-body counters) were considered. It reported that 167 workers had received doses over 100 mSv. Of these 135 had received 100 to 150 mSv, 23 workers 150-200 mSv, three more 200-250 mSv, and six had received over 250 mSv (309 to 678 mSv) apparently due to inhaling iodine-131 fumes early on, but these levels are below those which would cause radiation sickness.

Japan’s regulator, the Nuclear & Industrial Safety Agency (NISA), estimated in June 2011 that 770 PBq (petabecquerel) (iodine-131 equivalent) of radioactivity had been released, but the Nuclear Safety Commission in August lowered this estimate to 570 PBq. The 770 PBq figure is about 15% of the Chernobyl release of 5200 PBq iodine-131 equivalent. Most of the release was by the end of March 2011.

Tests on radioactivity in rice have been made and caesium was found in a few of them. The highest levels were about one quarter of the allowable limit of 500 Bq/kg, so shipments to market are permitted.

According to a Stanford research, radiation from Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster may eventually cause approximately 130 deaths and 180 cases of cancer, mostly in Japan.

What’s the future of the power plant?

Right after the disaster, automated cooling systems were installed within 3 months from the accident. A fabric cover was built to protect the buildings from storms and heavy rainfall. New detectors were installed at the plant to track emissions of poisonous gas.

Filters were installed to reduce contaminants from escaping the area of the plant into the area or atmosphere. Cement has been laid near to the seabed to control contaminants from accidentally entering the ocean. Efforts to control the flow of contaminated water have included trying to isolate the plant behind a 30-meter-deep, 1.5-kilometer-long “ice wall” of frozen soil, which has had limited success.

Decommissioning the plant is estimated to last 30–40 years. While radioactive particles were found to have contaminated rice harvested near Fukushima City in the autumn of 2011, fears of contamination in the soil have receded as government measures to protect the food supply have appeared to be successful. Studies have shown that soil contamination in most areas of Fukushima was not serious. Japanese reactor maker Toshiba said it could decommission the earthquake-damaged Fukushima nuclear power plant in about 10 years, a third quicker than the American Three Mile Island plant.

Is it possible to visit Fukushima?

Yes! The site of the largest nuclear disaster of the 21st century is now becoming a must-visit spot in Japan. A story not just worth sharing, but experiencing yourself, in a way that is completely safe. Explore with ChernobylX the silence of a ghost town with the calm sound of waves hitting the shore. It was this very sea that, in March 2011, rose up and caused a thousand year record tsunami. Destroying houses, cars, and lives, the damage from the tsunami was swift but long-lasting.

But Fukushima is now a success story, and one you can be a part of. Become one of the first international tourists who walks with our professional English-speaking guide through the streets of abandoned houses, cars and schools. Peek into the parts of Namie, Futaba and Tomioka towns in the process of being cleaned, touch the petals of cherry blossoms on once a lively street, taste the local delicacies in newly opened restaurants, learn about local handmade crafts and shake hands with the good people of these towns as they work hard to re-build their communities. You might witness moments where neighbors hug each other after years of not seeing each other.

If you’re ready to visit (with maximum safety, of course) the area surrounding the (in)famous Fukushima power plant, do it now, before it becomes as crowded as Chernobyl.

Book your tour with ChernobylX now!

ChernobylX

ChernobylX

x.tours

x.tours